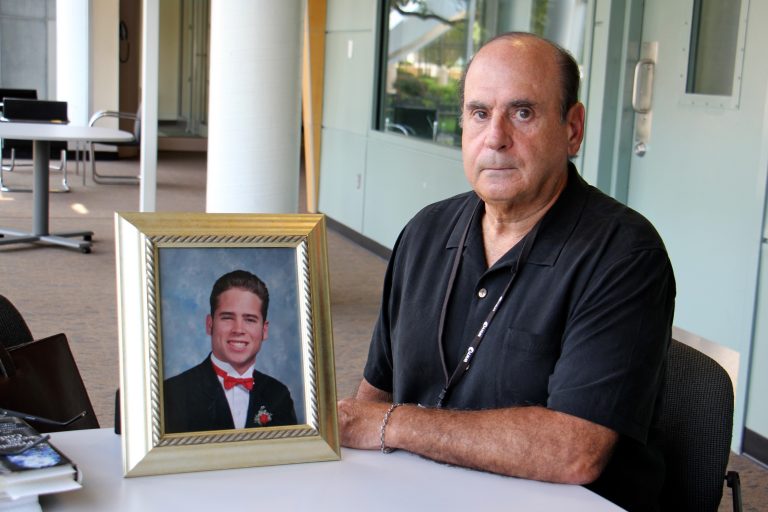

Photo of Art Baselice Jr. holding a portrait of his son, Arthur Baselice III.

By Karim Sharif, MSW & CHILD USA’s Social Work Intern, who collaborated with Art Baselice Jr. to write this story and honor the memory of his son, Art Baselice III.

“See, that’s my problem: too much respect”.

If you speak with Arthur Baselice Jr., you’ll believe it, too. While we talk, the retired Philadelphia detective’s undivided attention is on our conversation with intense, genuine engagement. Arthur’s presence commands respect – not to be confused with demanding it.

Arthur is sharp, present, no-nonsense, and yet tactful, inviting, level. He invites me to walk with him some time, and, at my request, clarifies where I can get a proper cheesesteak (you should only trust the opinion of a lifelong Philadelphian – even if they now live in South Jersey). When I ask what he’s up to lately, he conveys patient urgency and substantive, ripened anger:

“These days, we’re waiting and making it happen for as long as we can.”

The loss of Arthur’s only son, Arthur Baselice III, is no secret. Quite the opposite – since losing him, the elder Arthur commits much of his time and energy to fighting to hold his son’s abusers, and others like them, accountable. He’s been interviewed multiple times by NPR’s Philly annex, WHYY; he’s a vocal member among networks of survivors and those affected by sexual abuse, speaking for justice and to highlight the need for reparations and infrastructural supports for survivors. Art’s also a household name at CHILD USA: a long-time donor, regular attendee at any public-facing events such as rallies, and a continual reminder of who we’re fighting for.

Arthur Baselice III died of an overdose in 2006 at 28. His addiction was spurred at a young age by members of the clergy at his high school, Archbishop Ryan High School in Northeast Philadelphia. Clergy members would drug young Arthur in the course of sexually abusing him. Eventually, Arthur’s abusers – including his principal, Franciscan friar Charles Newman – deviously leveraged his struggles with addiction to ensure his continued silence about his abuse, providing him with access to drugs for many years after his graduation.

Struggles with addiction root from a variety of lived experiences; Arthur III’s traumatic experiences of sexual abuse would have been immeasurably painful with or without the involvement of drugs. Arthur III’s substance use was more than a way out of the pain. It stemmed from the cruelty of his abusers, who introduced and enabled his addiction: a testament to their lack of empathy or respect for the people – and children – they harmed.

A 2015 interview with WHYY includes Arthur Jr. recalling his last interactions with his son:

“I seen him the night that he went out. I said, ‘How you doing? You OK?’ He said, ‘Yeah.’ That was it,” said Baselice, choking back tears. The next morning, two detectives came to his house to tell Baselice the news about his son.1

It’s been an ongoing struggle to successfully reform the Statute of Limitations in Pennsylvania. The statute prevents the men who hurt Arthur’s son from being held accountable – though, even if they were found guilty, it couldn’t make up for the loss. (You can read more about Statutes of Limitation across the country on CHILD USA’s website).

Grief can be unwavering; anger fuels resolve.

Vengeance, however, is a journey all its own. It evolves. Art’s is not a bloodlust or an all-consuming rage, but the product of incomprehensible grief, compounded with years and years of insult to injury by those who took his son from him.

“At this point, revenge is making claims; revenge is exposing abusers.”

This unglamorous revenge is one of accountability and honesty, one that comes from the desire to be able to rest. Such a vengeance is, altogether, un-vengeful. Instead it’s a quest for justice – for the son whose face is tattooed on his left arm, the son whose ashes are in a bracelet on his right wrist. It’s the quest of a father who wakes up to a world his son is no longer part of. Arthur reiterates this while we talk – it is a weight that evolves for his family each day. They paid an unthinkable price, a price that traditional portraits of vengeance – ripe with grandeur, drama, and poorly-imagined morals – can’t alleviate the weight of. Arthur knows all the vengeance in the world won’t bring back his son. But he also knows justice can at least save the lives of others.

Collaboration and community are vital for this work; Arthur sees the similarities in the work CHILD USA does and his own quest for justice:

“We have the same objectives of accountability, transparency, and civilized, legal retribution. I believe in what CHILD USA is saying: this is a crisis, and social & civil rights actions need to be enforced.”

Justice is not inherently closure. Justice, at its core, is a matter of humanity; it is about the virtue and fairness our communities demand and the underlying ideal of doing what is right, stopping abuse for the future as much as for the present and past. It will take all of us working together. This humanity is achieved through action, reconciliation, and prevention. As Arthur says:

“Any man… any real, honorable man… that sees something like that would go straight to the cops; they would do whatever they could to stop it as soon as they found out. That’s what this is about: truth.”

Accountability and transparency, by other terms: truth. In action, they are the acceptance of truths of the abused, of the silenced. And, as Arthur says:

“If the truth kills something, then it probably deserves to die.”

Arthur’s words stand out. They pull you to the truth, and – like his demeanor – command attention, instead of demanding it; his words have a simple logic the grief behind them never will. This grief, though dense, is clear. Arthur mourns the son he cannot have, the son he could never replace. He mourns for his son, just as he mourns his son. And, as Arthur knows, reconciliation is as unlikely as true closure. In one interview with WHYY, he says:

“If I am successful in litigation. Is that check going to restore me? It’s going to punish them, but it’s not going to restore me. The only thing I can look for is a little bit of satisfaction […] This all boils down to one word: truth. I’m trying to expose it. They’re trying to hide it.”

Arthur’s perspective remains notably understanding and thoughtful in spite of his pain. He explicitly differentiates religious communities and practicing individuals from perpetrators of abuse, saying that it’s not faith that’s wrong, nor the religious – though, as he notes, it is an injustice to not believe and assist victims and survivors. Rather, there are perpetrators taking advantage of a system that enables them to manipulate communities and abuse children.

Child abuse and child sexual abuse are all too frequent. Are we all at fault when abuse happens? Or, is it on us to move our world toward ending it? For Arthur – and for our devoted team at CHILD USA – a system allowing abuse must be held accountable, and stopped.

“Religion, faith – it’s something good. But as soon as money gets involved… they’ve ruined it. Follow the cash flow, […] [members of the church are] treating abusers like royalty. […] You can’t accept blind faith; […] educate yourself, don’t believe everything at face value. Misplaced trust is the easiest path to destruction. […] The Church […] have made victims, like my son, ‘the enemy’. People don’t want to have their illusions shattered, because it’s so much easier to believe than the truth. It’s an illusion because it didn’t happen to them, it didn’t happen to their kids. Or maybe it did, but they don’t want to believe it.”

At this point, Arthur mentions again that he has too much respect. When I ask what he means, Art explains he, too, struggled to see the signs. Arthur is certain he would have acted immediately had he known, but often, it is the illusion of respect, of decorum, of not wanting to break rank, that makes us think we are powerless or mistaken. That illusion – demanding our respect, unlike Arthur’s command of it – allows abusers to harm our communities. Arthur has empathy for those afraid to break their illusions, but knows silence is not enough. Arthur wants accountability, because to shatter this illusion – to verify who has access to our children, to our families and friends – would help prevent what happened to Arthur III from happening to others.

“To do what they’ve done to our son, to others; kids…”

He trails off, but there really is no way to end the sentence.

* * *

During our conversation, I am captivated by Arthur’s willingness to dive in. Candid and frank, Art’s words are carefully deliberate, his tact distinct from an attempt at concealment. Perhaps that is the source of his willingness: the Baselice family has nothing to hide. They carry the grief, rage, and honesty that come with loss, that stoke searches for justice. Arthur’s statement – that if the truth kills something it probably deserves to die – is an idea he embodies.

Arthur does not shy from this transparency. Grief must be parsed over time; not for its remedy, but for its mitigation. When we discuss the holiday season, he does not hesitate to point out that my own visit with my parents is an experience he will never again have in his life. To say such is not an insult between us. It is reality; it is Arthur’s honesty and years of pain and processing at work. His words remind us both of what we are fighting for.

To just call the Baselice family heroic would be an insult to their grief. Where does bravery, heroism, or resolve factor into losing a son? Their bravery came after, in fighting for what’s right, even if it can’t undo their loss. The loss of Arthur Baselice III is one tragedy – one crisis – amidst an epidemic of abuse, grief, and loss caused by those who abuse children. Arthur’s bravery is knowing this firsthand, irreducibly, and seeking to prevent it for others. It’s his vocality for changing laws in Pennsylvania to benefit survivors and victims of child sexual assault. Heroism is honoring those we’ve lost by protecting those we haven’t yet.

“We have to do whatever we can to stop this, at every level. When we make these changes ourselves, it matters…. if we can set that pattern, we won’t keep going through this. I hope no one else has to do this. No one else has to go through this. It needs to end.”